Moving Through Digestion: The Stomach and MMC

The Stomach

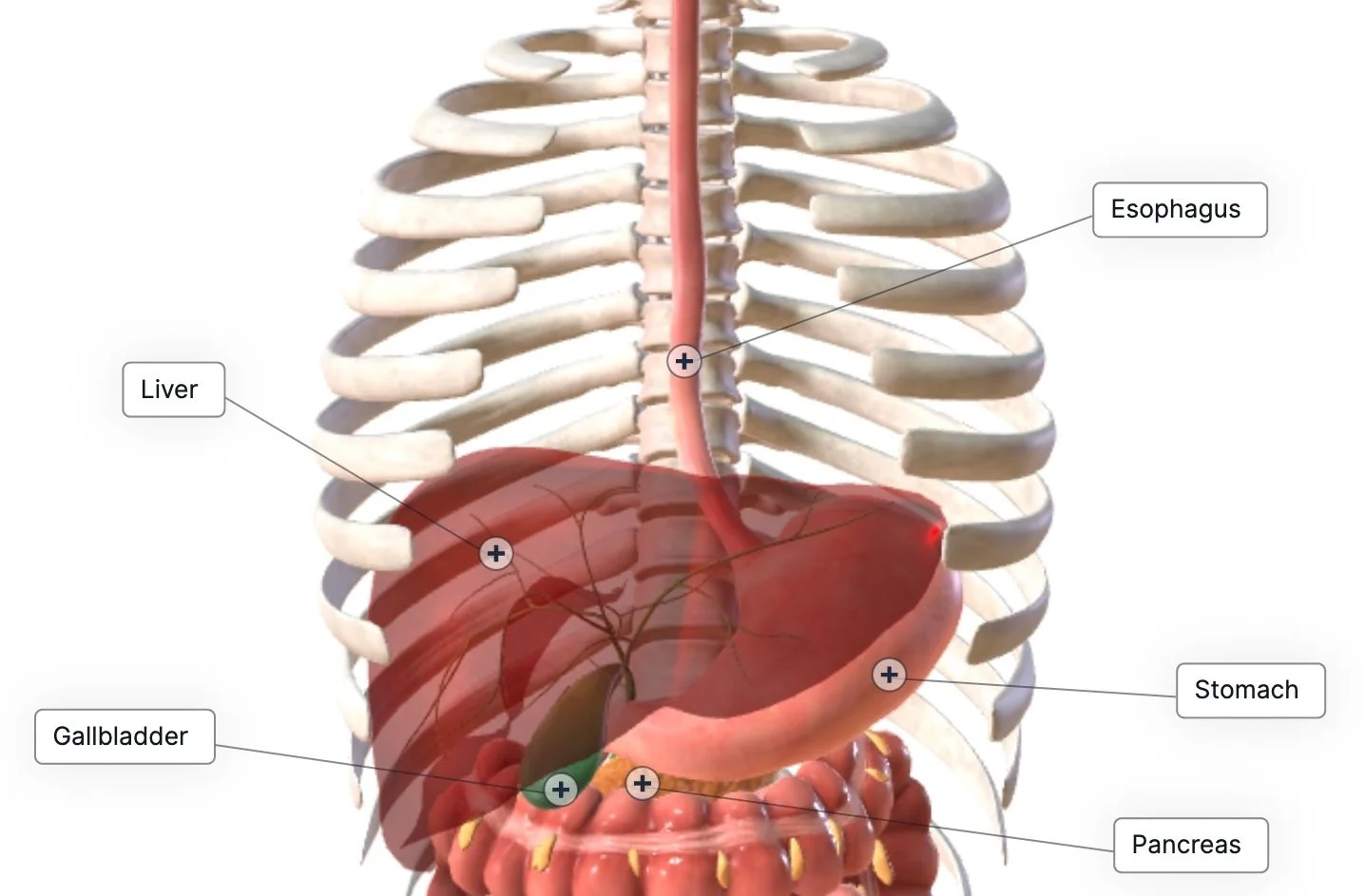

From the esophagus, we mosey on down to the stomach. Most of us have learned the expression “my stomach hurts.” And while sometimes, that’s accurate, the stomach doesn’t take up as much of the abdomen as we’ve been led to believe. The stomach looks like an asymmetrical jellybean on the left side of your upper abdomen. Half of it tucked behind your ribcage just behind a portion of your liver, but in front of the pancreas.

The stomach is a reservoir, an acid lake, and a trash compactor all in one.

Chewing our food gets it small enough to be swallowed, and it also gives the stomach acid more surface area to break that food down even further. The pH of the stomach is insane, somewhere between 1.5-3.5. Battery acid (which can dissolve bone and metal) is only a few steps down from that at a pH of 0. This is why we’re cautioned against brushing our teeth after we vomit. Part of that vomit includes stomach acid, which can weaken our enamel. But we need this acid, it helps break down proteins and destroy pathogens (bad microbes). This is why chronic anti-acid use (like PPIs) can lead to dysbiosis and SIBO (small intestinal bowel overgrowth).

The stomach makes its own hydrochloric acid, enzymes, intrinsic factor (important for vitamin B12 assimilation), and mucus. The mucus is key. Without it, there would be no buffer to protect the stomach from its own digestive juices. Ironically, symptoms of high or low stomach acid can be similar: bloating, burping, heartburn, and nausea. So, it’s important not to assume that heartburn is always from acid reflux.

The lower part of the stomach acts like a trash compactor. It has three layers of smooth muscle that alternately contract to help degrade and mix the stomach contents before they move on to the small intestines. It contracts about 3-5 times per minute, depending on autonomic tone. Parasympathetic tone stimulates the vagus nerve and increases stomach contraction, whereas sympathetic stimulation of the solar plexus (aka celiac plexus) decreases stomach contraction. This is why you hear so much about the parasympathetic system and the vagus nerve. Parasympathetic is known as the “rest and digest” side, and the sympathetic is referred to more as the “fight or flight” side. If we’re in chronic states of stress and high alert, these stomach contractions won’t happen, meaning that food in our tummies doesn’t get properly mixed and mashed before going into the small intestine.

The MMC: The motor motility complex

Remember how I was talking about timing being crucial? Another example of that is the MMC, the Migrating Motor Complex. It’s another form of peristalsis like we learned about with the esophagus, but here, it happens during fasting times. It’s a rhythmic pattern of gastric movement from the stomach to the last section of the small intestine over an hour-and-a-half to two-hour window. This is also why it’s not recommended to graze throughout the day (unless low blood sugar deems it necessary). This is the body’s housekeeping window where it moves indigestible food, cellular debris, and bacteria through the GI tract. The MMC also plays by circadian rules and is significantly reduced at night. This is also why it’s often suggested not to eat a big meal before bed. It’s going to take a long time to move through your gut, making fermentation and discomfort more likely.

Continue the Journey

Keep learning with me as we continue through the digestive track. Subscribe below, add me to your contacts & follow me on social media for more engaging content on natural and energetic health. I’ll release a new body series post each week. I hope they inspire you to get to know your body and all its functions. I also invite you to ask me your questions on natural and energetic health.